|

||||

|

Olympic swimmer recalls summers on Liberty Lake

7/27/2011 10:33:31 AM

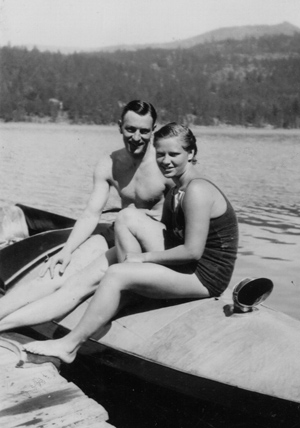

Submitted photo

Mary Lou relaxes on the dock of her family's cabin with her future husband, Robert Skok, in 1933.

By Kelly Moore

Splash Staff Writer

Almost 75 years to the day she first saw it in person, she remembers Adolf Hitler's serious scowl. She remembers Jesse Owens' dance moves and the lighting of the first-ever Olympic flame. What she recalls even more fondly is Liberty Lake.

Born in Spokane, the swimmer honed her skills every summer in the cool mountain waters at the foot of her family's lake cottage. Here, her Olympic dream was born.

"I just walked in the water and that was it," Petty-Skok said. "I just loved it."

Summers at the Petty cabin

From Memorial Day to Labor Day every year from 1916 to 1937, Petty-Skok and a handful of her dearest friends spent their summers stirring up mischief on the wild shores of Liberty Lake.

"We had absolute free reign," Petty-Skok said. "There was no vandalism or violence. We could go anywhere, and we weren't afraid of anything."

Her parents pulled a houseboat ashore on MacKenzie Beach in 1916, and by the next summer, the family was ready to move into their cottage on Dreamwood Bay. At that time, only three cottages - all built by her father - existed there. The three families had six kids, all close in age, and all friends.

"We were busy all the time," Petty-Skok said. "We made water skis by nailing shoes to boards. … We lived in the water and in the sun. It was absolutely beautiful."

She said visitors to the nearby Dreamwood Bay Resort would often rent boats and abandon them in the middle of the lake to skip out on the bill. For fun, the kids would retrieve boats. Perhaps in a case of too much fun, the group accidentally sent one of the boats straight to the bottom of the lake.

"They were supposed to be sink-proof," Petty-Skok laughed. "There was an air tank under the front seat to keep the boats from sinking. Well, of course we didn't mean to, but we got to rocking and playing and before long that boat was completely under water."

Petty-Skok said her friends often visited her family cabin on Dreamwood Bay. Whether they were old pals from high school or, later, Olympic teammates in town to train, everyone slept on the floor of the one-room cabin, and "they loved it."

"We had a wood range in the corner, and my mother would bake all day," Petty-Skok said. "We'd come in for lunch and eat a cake in one sitting, and there'd be another one for dinner. … Of course, that was before the Great Depression hit."

An Olympic dream takes shape at Dreamwood Bay

Submitted photo

The Petty cabin (center), just a half mile from the Dreamwood Bay Resort, was home to Mary Lou Petty-Skok and her family every summer from 1917 to 1937.

Bunking with a Hollywood starlet

By Kelly Moore

Splash Staff Writer

"Two notable things came out of the 1936 Olympics: Jesse Owens and Eleanor Holm," Olympic swimmer Mary Lou Petty-Skok said.

Although known less for her achievements and more for getting suspended from the Olympic swim team just weeks before the games, Holm made headlines that year nonetheless. Petty-Skok was the 1932 gold medalist's cabin mate on the SS Manhattan to Berlin.

"She was the kind that could party all night and set a record in the morning," Petty-Skok said.

Holm was kept locked on the lower deck along with the 350 other American athletes, but Petty-Skok said reporters would find ways to sneak her into first-class parties, sending her to bed inebriated at the end of the night.

"Our coach told her he'd kick her off the team if she kept doing that," Petty-Skok said. "Sure enough, she did it again and he followed through on his word."

Holm outlived her infamous Olympic showing and went on to have a high-profile celebrity career as an actress and singer co-starring as Jane in a Hollywood production of "Tarzan."

Visiting Liberty Lake wasn't all just fun and games. During the school year, Petty-Skok swam early-morning and late-afternoon laps at the Elks Club in Spokane. When summer hit, she only picked up the pace.

"Ever since I was 8 years old, I wanted to be in the Olympics," Petty-Skok said. "I don't know why, but I did. I had to explain to my friends at school what it was."

During her summers on the lake, she said she'd swim from Dreamwood Bay across the lake to MacKenzie Beach, her father watching with a stopwatch and binoculars. If she met the competitive time she was aiming for, her father would wave a flag to let her know she could swim back at her leisure. If she missed her mark, she'd have to try again. Eventually, she and her father were able to communicate beach to beach by telephone.

"There wasn't much time to talk," she said. "But we could say, ‘Yes. Good job.' or, ‘No. Try again.'"

She started swimming competitively when she was 13, and no one in Spokane could touch her. At the age of 17, she earned a spot in the 1932 Olympic trials but, as it did for many families, the Great Depression had cleaned the Pettys dry. Without financial backing, she declined the invitation and watched two girls she'd already beaten take spots on the Olympic team.

Another chance came when she was offered a spot on the Washington Athletic Club's swim team based in Seattle in 1934. She left behind Spokane and her fiancé, Robert Skok, took a job across the state at Montgomery Ward and started setting national records.

"When I got a second chance, oh, it was just heavenly," she said.

Even so, she made sure to come home every chance she got. The roundtrip train ride from Seattle to Spokane cost about 12 cents, and the familiar waters of Liberty Lake became another training ground for her and a handful of future Olympic teammates.

And while he lacked the skill and competitive drive to keep up, Skok, who had a "marvelous sense of humor," joined in as well.

"He loved the water, too, but he couldn't swim for nothing," she laughed. "We had a little boat at our cottage, and I'd take a tow rope and tie it around my waist. I'd pull the boat behind me while I swam and that slowed me down to about his pace. So we'd swim side by side around the lake and have a great time."

Her hard work paid off. In 1936, she qualified for the Olympic team at the Astoria, N.Y., trials. That August, she'd be on her way to Berlin, Germany, for the experience of a lifetime.

The journey to Berlin

"There was no money available at that time," Petty-Skok said. "Women didn't get anything. Almost all the guys had scholarships at universities, so their expenses were paid. It was a different story for us."

Her mother and aunt walked the streets of Spokane with a tin cup asking people to help send her to Germany. She said Spokane was a lot smaller then, and her family was well known, so the panhandling was more of a joke.

"They just giggled and laughed and they got about $15 out there," Petty-Skok said.

She also raised money selling pictures and swimming in exhibitions - anything to raise a buck. The Spokane Elks Club also donated money to her efforts.

High school friends from the Kappa Chi Social Club tried raising funds at a dance in the Dance Pavillion on Liberty Lake. Her husband-to-be played in the band that night.

"I don't remember if they made any money that night, but I know those girls would have done anything for me," she said.

With $75 in her pocket, Petty-Skok made her way to New York, where she and 350 other U.S. Olympians boarded the SS Manhattan.

Many of the athletes got sick on the eight-day journey to Germany while they were kept locked away in the lower decks, away from first-class passengers. Still, conditions on the boat were better than what many of the Depression-wracked athletes had grown used to.

The swimming pool was an iron tank "in the bowels of the ship," too fetid to train in after only four days.

"There were few complaints," Petty-Skok said. "When you get there, you don't complain. The conditions weren't great, but there was food all the time, and we enjoyed each other because nothing else was provided."

For entertainment, the hoards of athletes shared one ping-pong table and one volleyball net. She said they'd play games at the ping-pong table with 10 or 12 people at a time, everyone sharing the two paddles.

That's when she met American track legend Jesse Owens.

"At that time, he was just like everyone else," Petty-Skok said. "We were all national champions."

She said all the athletes mingled together on the ship, paying no attention to race -different from the way things were in much of the country they represented. Everyone did everything together, although the "track boys," who were wonderful dancers, never asked anyone to join them.

1936 Olympics

By The Numbers:

Berlin, Germany, Aug. 1-16, 1936

11th Olympic Games

49 nations competing

3,632 male athletes

331 female athletes

129 events in 19 sports

24 gold medals for the U.S. (56 total)

Submitted photo

Now 96, Mary Lou Petty-Skok lives in a retirement community in Tempe, Ariz. She exercises five times a week and volunteers in her spare time.

Swimming in Hitler's Games

The Olympic Games were awarded to Berlin in 1931, two years before Adolf Hitler rose to power. By 1934, word of his anti-Semitism had started to spread, and some called for a boycott of the games.

"We didn't realize at that time the severity of it," Petty-Skok said. "To me, Hitler was just another dictator. We'd seen Stalin, Mussolini, Tito. They were all dictators. Hitler was just another one. We had no idea what he had in mind."

At the opening ceremonies, she remembers standing in the stadium lined up by country waiting an hour and a half for Hitler to arrive. As he entered the stadium, he came within about 15 feet of her, but that's not what left the most lasting impression.

What she remembers is giggling with the Hungarian athletes and overcoming language barriers to spread the game of "rock, paper, scissors." And recalling when the torchbearer lit the Olympic flame still gives Petty-Skok a chill.

"The runner came in and climbed up all those steps, then whoom!" she recalled. "I don't think there was a dry eye in the place."

The games lasted 16 days and before swimming events started, she remembered seeing Hitler at the track and field stadium every day. However, he left right after Owens won his first of four gold medals, then reappeared poolside about a week later.

"He had a place right down on the deck," Petty-Skok said. "I never saw him smile. He was always very serious. People always adored him, though."

At a banquet, her team listened to a 45-minute speech from Hilter without an interpreter.

"We didn't understand a word he said, but none of us moved a muscle the entire time," Petty-Skok said. "We were mesmerized. Just the articulation - it was fascinating to watch."

Two days after coming down with food poisoning, Petty-Skok finished fourth in her event, just seconds away from the bronze medal. She retired from swimming the day she set foot back on American soil. Skok, her fiancé of three years, took money from their hope chest to fly to New York and surprise her, and they were married that day.

Another chapter

The couple moved to southern California a few short years later, where they raised two daughters. Later, they moved to Arizona, where Skok passed away in 1998. Her children, seven grandchildren and 17 great-grandchildren remain.

Petty-Skok now lives in a retirement community, where she exercises five times a week, volunteers in the kitchen every morning and bartends all the parties.

She looks back on her years as a champion swimmer with fondness, but has no regrets leaving it behind. When recalling those days, she said she feels like she's talking about someone else.

"I'm humbled," she said. "I just did it because it was a kind of selfish thing I always wanted to do. … Getting to talk about it now is just frosting on the cake."

Blessed with an athletic bent, Petty-Skok took up competitive golf in the late 1940s and played for decades, working her way down to a handicap of 9.

"My life has been one wonderful chapter after another," she said. "The swimming was a chapter; the golfing was another chapter; when we got married that was a chapter and when our daughters married that was another chapter. We've always made the best of everything we've done, and I still am. This is just another chapter."